20 August 2019

John Allison's review of Moniuszko's Paria

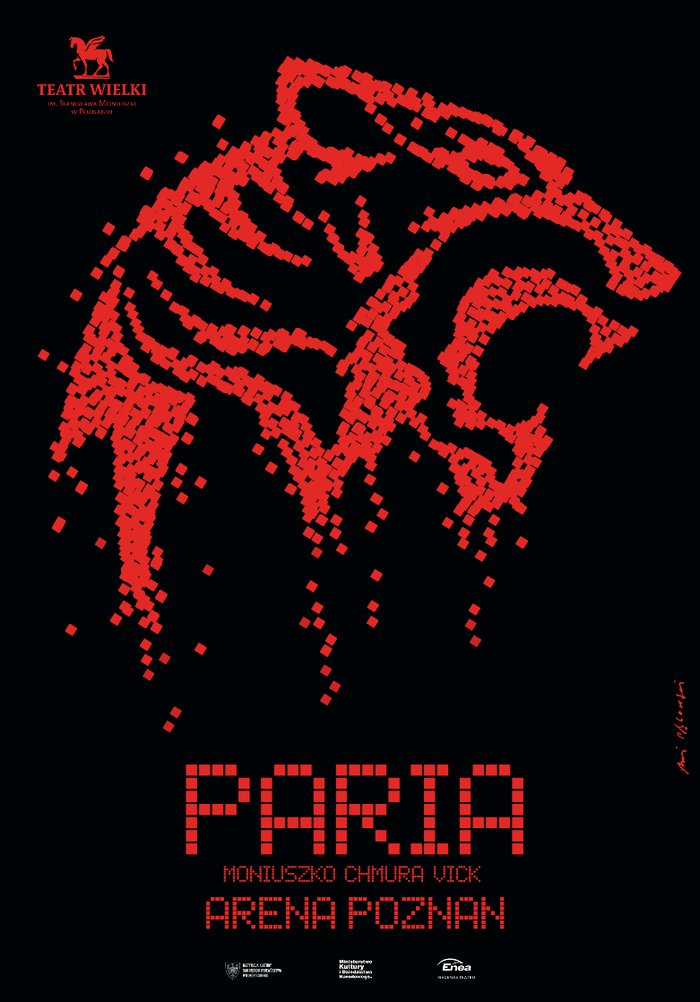

Moniuszko’s last opera, Paria, doesn’t entirely fit with the picture we have of the composer as the ‘father of Polish opera’, but then it is a work perhaps destined by its subject matter to fall between stools of public taste. As the only one of Moniuszko’s mature works to have a non-Polish setting, to 19th-century audiences in partitioned Poland it may have lacked the stirring patriotic message of his more popular operas and it is little wonder that it all but vanished in the aftermath of its 1869 premiere, while outsiders may equally have looked in vain for the appealing Slavonic colour found in such masterpieces as Halka and The Haunted Manor. But it has never seemed quite so cosmopolitan in its outlook as in Graham Vick’s new production (June 28) for Poznań’s teatr wielki. Rescuing it from its surface hokum—the story, which to many will suggest a cross between Les Pêcheurs de perles and Aida, is based on the same Casimir Delavigne source that had already found operatic expression in Donizetti’s Il paria—Vick put its subject of intolerance under the spotlight, with the result that one came away with increased admiration for the power and universality of the work.

Following David Pountney’s staging of The Haunted Manor in Warsaw in 2015, Vick is only the second non-Polish director of international standing to tackle a Moniuszko opera, and he seized the opportunity to give it one of his trademark immersive, audience-promenading productions, along the lines of his Stiffelio in Parma two years ago. His original plan had been to stage Paria in a former synagogue, but when that fell through the production was moved to Poznań’s arena, an indoor sports hall. An army of extra actors—all carrying signs identifying them as outcasts in some way or other—had first been encountered banging on locked doors along the claustrophobic corridor through which the audience had to enter. As Vick put it in the programme, we see the effects of ‘family fascism’ here, with two fathers stuck in their respective dogmas. The heroine, Neala, is a Brahmin priestess and the daughter of the Brahmin high priest, Akebar. Her marriage to Idamor, the warrior who has defended the country, is abandoned to fatal effect when he is revealed to be the offspring of Dżares, the old low-caste Pariah who has come in search of his long-lost son.

The sectarian nature of the plot was highlighted in Samal Blak’s costumes, which turned the women’s chorus into handmaiden-nuns, and the male followers of Akebar, all wearing fluorescent halos, sat in a circle reminiscent of other operatic temples. Akebar’s prophesies were written in the LED lights of the Arena’s scoreboard, and cultish photographs of the leader were distributed to the milling spectators. Under alienating bright lights, a chorus of gun-toting zombies swept around, and the floor of the Arena was dotted with perspex sweatshops in which actors toiled away under a spotlight. Poland has, of course, a very adventurous theatre tradition, and even if this audience had not encountered a production quite like it, the public was clearly receptive to Vick’s method and message. Inevitably, an audience on the move cannot absorb music with undivided attention, but the score provided its own cues—including the lengthy, unusually placed overture, which comes between the Prologue and Act 1, and is the best-known music from the opera. Its wonderful themes registered strongly here in an excellent performance under the company’s music director, Gabriel Chmura, who held everything together with long-distance mastery. The enjoyable ballet music in Act 3 was excitingly marshalled by the choreographer Ron Howell in the form of ‘breakout’ ensembles around the hall and in between pockets of the audience. Thanks to some audience participation, the whole place felt choreographed in the wedding scene.

Paria may not ultimately represent the best of Moniuszko’s musical genius, but it was a measure of the performance’s success that the work seemed so potent here. In this setting, musical niceties could have got lost, yet right from the tenor’s first aria, with Dominik Sutowicz bringing impressive heft and ringing power to Idamor, it was clear that interpretative insights and subtlety were possible. Monika Mych-Nowicka gave a sympathetic and touching performance as Neala, her soprano gleaming brightly in her cavatina and romanza set-pieces. Szymon Kobyliński supplied dark, bass-baritonal resonance as Akebar, and in a warmly sung performance Mikołaj Zalasiński conveyed all the pathos of Dżares. When stocktaking is done on this Moniuszko bicentenary year, on account both of its political importance and its artistic values Poznań’s Paria will surely count as one of the key events.

John Allison, „Opera” (September 2019)